Введение

Завершившаяся пандемия новой коронавирусной инфекции (COVID-19), вызванной вирусом SARS-Cov-2, оказалась особенно безжалостной к пациентам отдельных групп. Опыт, накопленный в исследованиях последних лет, показал, что люди, страдающие различными хроническими заболеваниями, подвержены более высокому риску инфицирования SARS-Cov-2, и большинство больных COVID-19 имеет отягощенный анамнез [1].

В когорте из 1590 больных COVID-19 из Китая W.J. Guan et al. выявили, что у 399 (25,1%) пациентов было по крайней мере одно сопутствовавшее заболевание, у 130 (8,2%) – 2 или более сопутствовавших заболеваний. Артериальная гипертензия (16,9%), сахарный диабет (8,2%), сердечно-сосудистые заболевания (3,7%) и хроническая болезнь почек (1,3%) были наиболее распространенными сопутствовавшими заболеваниями у всех пациентов с COVID-19 [2]. N. Chen et al. также сообщили, что 51% (50/99) пациентов с COVID-19 имели сопутствовавшие заболевания, включая сердечно-сосудистые или цереброваскулярные (40,4%), сахарный диабет (12%), заболевания пищеварительной системы (11%) и злокачественные опухоли (0,01%) [3]. Многие исследования продемонстрировали, что тяжелые формы COVID-19 чаще ассоциируются с наличием сопутствующих заболеваний, таких как сердечно-сосудистые заболевания [4, 5], артериальная гипертензия [6, 7], сахарный диабет [4–6], хроническая обструктивная болезнь легких (ХОБЛ) [5–8], злокачественные новообразования [5, 7], цереброваскулярные заболевания и хроническая почечная недостаточность [9].

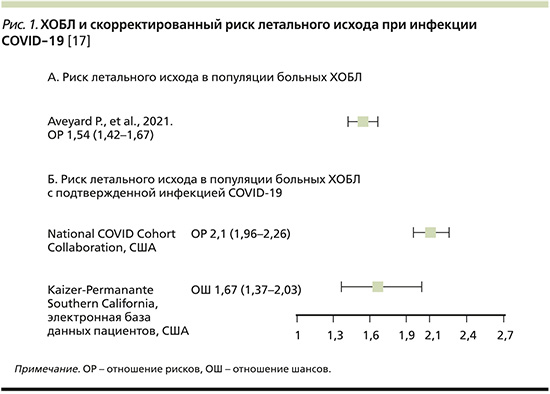

Распространенность ХОБЛ среди пациентов с COVID-19 может составлять 1,5–2,9% [6, 10, 11], что ниже, чем распространенность ХОБЛ в общей популяции [12]. Однако по сравнению с общей популяцией пациенты с ХОБЛ, инфицированные SARS-CoV-2, как правило, имеют более высокую смертность (рис. 1), худший прогноз [13] и часто нуждаются в респираторной поддержке [14]. Проведя анализ данных 1592 пациентов с COVID-19, G. Lippi et al. обнаружили, что ХОБЛ достоверно коррелировала с тяжелым течением COVID-19 (отношение шансов [ОШ]=5,69; 95% доверительный интервал [ДИ]: 2,49–13,00) [15].

В рекомендациях Глобальной инициативы по ХОБЛ (GOLD) также подчеркивается, что пациенты с ХОБЛ относятся к группе высокого риска в отношении неблагоприятных исходов COVID-19 [16].

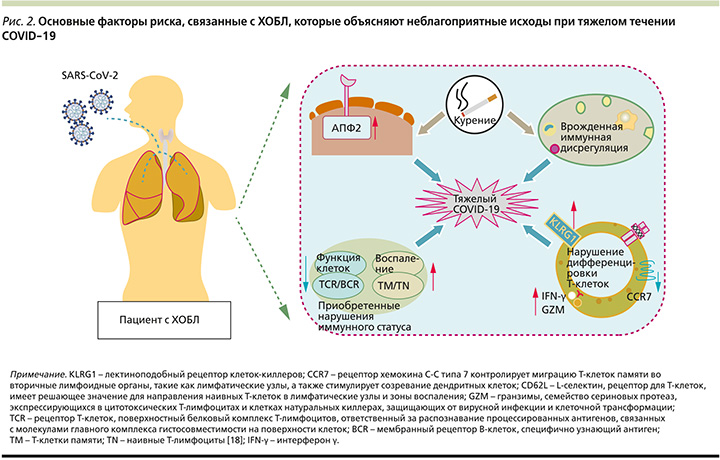

В попытке ответить на вопрос, почему пациенты с ХОБЛ подвержены тяжелому течению COVID-19, эксперты предлагают обратиться к изучению различных аспектов, включая экспрессию ангиотензинпревращающего фермента 2-го типа (АПФ2), курение, врожденную иммунную дисрегуляцию, приобретенные нарушения иммунного статуса у пациентов с ХОБЛ (рис. 2).

В этом обзоре рассматриваются некоторые аспекты взаимного влияния ХОБЛ и COVID-19, обусловливающие неблагоприятные исходы. Также представляются данные по эффективности отдельных способов медикаментозной терапии, в частности муколитической терапии, улучшающих течение ХОБЛ.

Связи между ХОБЛ и COVID-19

Несмотря на продолжающееся в настоящее время активное изучение проблемы, допандемические исследования показывают, что может существовать несколько механизмов, объясняющих, почему у пациентов с ХОБЛ часто развивается быстрое и значительное ухудшение состояния во время инфекции COVID-19. Среди них – усугубление обструкции дыхательных путей, более высокий риск коинфекции, вызванной другими патогенами, такими как условно-патогенные бактерии и вирусы, высокая вероятность усиления системной воспалительной реакции на фоне предсуществующего хронического воспаления, возможная пролонгированная репликация вируса на фоне избыточного накопления активных форм кислорода, окисления липидов и повреждения ДНК, повышенный риск микротромбозов [19].

Дисфункция врожденной иммунной системы. Врожденная иммунная система является первой активной линией защиты от вирусных инфекций [20]. S-белок вируса SARS-CoV-2 активирует врожденный иммунный ответ путем рекрутирования нейтрофилов, макрофагов и моноцитов, которые стимулируют выработку цитокинов. Однако дисфункция врожденного иммунитета у пациентов с ХОБЛ может приводить к тому, что провоспалительные факторы, такие как активные формы кислорода, интерлейкин-6 (ИЛ-6), GM-CSF (Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor), матриксные металлопротеиназы и хемокины, способствуют повреждению легких и усилению каскада воспалительных реакций вместо того, чтобы способствовать элиминации вируса. К таким же неблагоприятным последствиям может приводить длительная и избыточная выработка интерферонов макрофагами [21]. Также у пациентов с ХОБЛ наблюдается более высокая, чем у здоровых людей [22], экспрессия макрофагов M1 фенотипа, что индуцирует высвобождение провоспалительных цитокинов, таких как фактор некроза опухоли-α (ФНО-α), ИЛ-1 и ИЛ-6, поляризацию Th1 и Th17, что способствует усилению воспаления. Кроме того, макрофаги при ХОБЛ характеризуются более низкой фагоцитарной активностью.

В периферической крови пациентов с тяжелой формой COVID-19 выявлялся высокий уровень CD14+, CD16+ моноцитов, вовлекаемых в патогенез инфекции и секретирующих различные провоспалительные цитокины, включая GM-CSF, MCP1, IP-10 и MIP1a [23]. Важно отметить, что число CD14+, CD16+ моноцитов у пациентов с ХОБЛ может быть значительно увеличено.

Результатом дисфункции компонентов врожденной иммунной системы пациентов с ХОБЛ стало снижение антиинфекционной активности, нарушение презентации антигенов, нарушение цитотоксичности естественных клеток-киллеров, ослабление взаимодействия с адаптивной иммунной системой, избыточное иммунологическое повреждение легких [24].

АПФ2. АПФ2 является важной регуляторной молекулой ренин-ангиотензиновой системы, опосредующей противовоспалительные реакции и вазодилатацию, катализируя превращение ангиотензина II в ангиотензин 1–7 [25]. Все больше данных свидетельствуют о том, что АПФ2 играет защитную роль в функционировании эндотелия и легких. Вместе с тем существует отрицательная корреляция между экспрессией АПФ2 и тяжестью COVID-19 [26]. Вирус SARS-CoV-2 не только использует АПФ2 в качестве рецептора, но и в дальнейшем модулирует его активность, снижая экспрессию АПФ2 в тканях, что приводит к накоплению ангиотензина II и ослаблению протективных эффектов ангиотензина 1–7. Примечательно, что снижение тканевой формы АПФ2 по сравнению с растворимой вызывает дисбаланс в иммунной системе, индуцируя выделение массы провоспалительных цитокинов, что способствует формированию «цитокинового шторма» [27].

В настоящее время нет исчерпывающих данных об уровне экспрессии АПФ2 у пациентов с ХОБЛ. В отдельных исследованиях анализ образцов легочной ткани и бронхоальвеолярного лаважа показывает, что экспрессия АПФ2 у пациентов с ХОБЛ и здоровых людей не имеет существенных различий [28]. Однако проведено значительное число работ, в которых сообщается, что экспрессия АПФ2 в эпителиальных клетках пациентов с ХОБЛ значительно выше, чем у здоровых лиц контрольной группы, и отрицательно коррелирует с объемом форсированного выдоха в первую секунду (ОФВ1) [29].

Курение Курение является основным фактором риска развития и прогрессирования ХОБЛ, индуцируя хроническое воспаление. Вместе с тем появляется все больше данных о неблагоприятном течении COVID-19 у курящих больных. Так, анализ серии случаев COVID-19 (n=2002) показал, что постоянное длительное и продолжающееся курение было связано с тяжелым и прогрессирующим течением инфекции, требующим перевода в отделение реанимации и интенсивной терапии: ОР составило 1,98 (95% ДИ: 1,29–3,05) [30].

В результате других исследований у пациентов с COVID-19 в Китае (n=1085) и Соединенных Штатах Америки (n=6637) подтверждено, что риск инфицирования SARS-CoV-2 или тяжесть течения инфекции коррелируют со статусом курения [31], что чаще приводит к неблагоприятным исходам [32].

Курение может не только увеличивать экспрессию провоспалительных цитокинов, таких как ИЛ-6, ФНО-α и ИЛ-17, в легких мышей, но и индуцировать экспрессию ангиотензина II [33]. Токсические компоненты табачного дыма также могут вызывать разрушение барьера слизистой оболочки, некроз клеток респираторного эпителия, разрушение ресничек, персистирующее воспаление и пролонгированную репликацию вируса [34]. Курение также связано с повышенной экспрессией АПФ2.

Дисфункция Т-клеток. Лимфопения и дисфункция Т-клеток коррелируют с тяжестью течения COVID-19 [35]. Вместе с тем воспаление при ХОБЛ характеризуется повышением числа нейтрофилов, макрофагов и Т-лимфоцитов (особенно CD8+) в различных отделах дыхательных путей и легких. Это происходит на фоне снижения регуляторных Т-клеток CD4+CD25+FoxP3, предотвращающих иммунную реакцию, что может быть генетически детерминировано [36]. Эти наблюдения указывают на дисфункцию Т-клеток при ХОБЛ, что выражается в снижении дегрануляции Т-клеток легких в ответ на гриппозную инфекцию и уменьшении продукции цитокинов Т-клетками после активации рецепторов Т-клеток [37, 38]. Дисфункция Т-клеток, преждевременная дифференцировка Т-клеток могут приводить к неадекватной защите и неадекватному воспалительному ответу при инфицировании SARS-CoV-2, делая пациентов с ХОБЛ более уязвимыми к тяжелым последствиям COVID-19.

Возраст. Еще одним важным фактором эксперты называют возрастные особенности функционирования иммунной системы, которые можно в полной мере адресовать к значительной когорте больных ХОБЛ старшего возраста. Изучено, что возраст является независимым фактором риска развития тяжелых форм COVID-19 [39–41]. Смертность увеличивается среди лиц старше 65 лет, причем на больных в возрасте 65–79 лет приходится 44% всех смертей, а на больных в возрасте 80 лет и старше – 46%. Иммуносупрессия, вызванная «старением» иммунной системы, характеризуется уменьшением не только числа лимфоцитов, но и разнообразия, а также сродства Т-клеточных и В-клеточных рецепторов [42]. Это приводит к снижению функции Т-клеток и повышенной цитотоксичности, снижению распознавания патогена, хемотаксиса и фагоцитоза макрофагов, естественных киллеров и нейтрофилов [43]. Таким образом, быстрое истощение и снижение функционального разнообразия Т-клеток могут обусловливать тяжелое прогрессирующее течение COVID-19 [44].

Патогенетические особенности, определяющие неблагоприятные исходы COVID-19 у пациентов с ХОБЛ

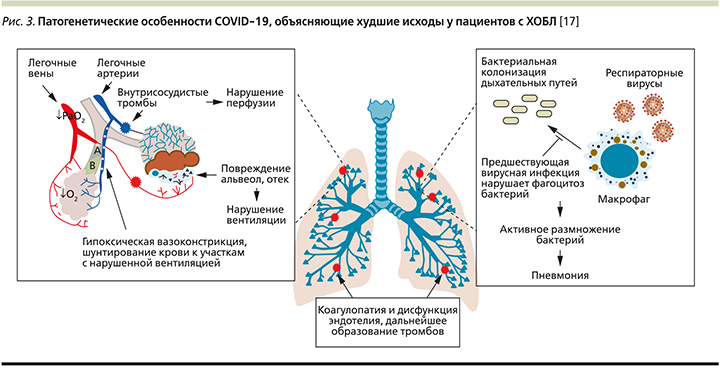

Характерным звеном патогенеза COVID-19 являются гипоксемия на фоне поражения легочной ткани, диффузное повреждение и отек альвеол, тромботические осложнения, нарушения вентиляционно-перфузионных отношений [45]. Несоответствие вентиляции/перфузии связано с гипоксической легочной вазоконстрикцией, что ограничивает приток крови к участкам с нарушенным газообменом и вызывает внутрилегочное шунтирование крови в другие области [46]. Исследования показали, что увеличение внутрилегочного шунтирования может быть связано с неблагоприятными исходами COVID-19, включая более высокую смертность [47]. Предсуществующие нарушения вентиляции легких на фоне патологии мелких дыхательных путей и эмфиземы снижают компенсаторные возможности при ХОБЛ, что усугубляет шунтирование и нарушение вентиляционно-перфузионного отношения [48].

Гипоксическая вазоконстрикция у пациентов с ХОБЛ, возникающая вследствие нарушения вентиляции, создает условия для агрегации тромбоцитов и повышает риск тромбообразования [49, 50]. Дальнейшее ремоделирование сосудов связано с усилением легочной гипертензии при ХОБЛ [51]. Описанные патофизиологические особенности также способствуют более тяжелому течению COVID-19, поскольку тромботические осложнения, в т.ч. легочная тромбоэмболия, типичны для некоторых форм новой коронавирусной инфекции в связи с гиперкоагуляцией крови и дисфункцией эндотелиальных клеток [52].

Существует еще один важный фактор, делающий пациентов с ХОБЛ более уязвимыми при инфицировании вирусом SARS-Cov-2. Частота вторичной бактериальной инфекции в целом невелика среди пациентов с COVID-19, однако ее развитие приводит к более серьезным исходам [53]. Вместе с тем у пациентов с ХОБЛ в стабильном состоянии отмечается колонизация дыхательных путей патогенными бактериями, что приводит к увеличению микробной нагрузки и обострению ХОБЛ на фоне респираторной вирусной инфекции [54, 55].

Таким образом, существует множество механизмов, объясняющих худшие исходы COVID-19 у пациентов с ХОБЛ. Среди них наибольшую роль играют повышенный риск микротромбозов, последствия внутрилегочного шунтирования и вероятность вторичной бактериальной инфекции (рис. 3).

Ведение пациентов с ХОБЛ в период значительной заболеваемости COVID-19

В условиях постпандемической заболеваемости COVID-19 лечение хронических респираторных заболеваний, в т.ч. ХОБЛ, представляет определенные проблемы. Врачебное сообщество, занимающееся помощью больным ХОБЛ, постоянно сталкивается с вопросами, касающимися диагностики заболевания (в т.ч. с безопасностью использования функциональных методов) и своевременной диагностики обострений ХОБЛ, возможности безопасного использования тех или иных ингаляционных устройств, необходимости применения системных и ингаляционных глюкокортикостероидов, безопасности методов респираторной поддержки и многими другими.

Не вызывает сомнений, что в условиях высокого риска инфицирования важно обеспечить полноценное фарамакологическое лечение ХОБЛ, а также использовать методы профилактики (такие, как вакцинация против гриппа и пневмококковой инфекции) и реабилитации для предотвращения развития любого обострения заболевания. Эксперты GOLD единодушны во мнении, что адекватная поддерживающая терапия ХОБЛ должна рассматриваться в качестве основного инструмента, способного предотвращать развитие обострений [12, 56].

Особую озабоченность вызывают диагностика и лечение обострений ХОБЛ с целью уменьшения риска госпитализаций и неблагоприятных исходов. Дифференцировать симптомы инфекции COVID-19 от симптомов обострения ХОБЛ может быть непросто. Если есть подозрение на COVID-19, следует рассмотреть возможность тестирования на SARS-CoV-2 [57]. Усиление кашля и одышки является частым признаком обострения ХОБЛ. Вместе с тем кашель и одышка встречаются более чем у 60% пациентов с COVID-19, но обычно также сопровождаются лихорадкой (более 60% пациентов), усталостью, спутанностью сознания, диареей, тошнотой, рвотой, мышечными болями, аносмией, дисгевзией и головными болями [58].

Ведение обострений ХОБЛ в период пандемии COVID-19

При развитии обострения ХОБЛ без инфицирования SARS-CoV-2 следует соблюдать терапевтические рекомендации, которые не теряют актуальности и во время пандемии COVID-19 [59, 60]. Несколько классов препаратов рекомендованы для скорейшего устранения симптомов обострения и снижения риска тяжелого течения и осложнений, к ним относятся в первую очередь бронходилататоры, глюкококортикостероиды, антибиотики, а также мукоактивные препараты.

Бронхолитики. Ингаляционные β2-агонисты короткого действия (КДБА) и антихолинергические препараты короткого действия (КДАХ) остаются основой облегчения симптомов и уменьшения ограничения воздушного потока во время обострений ХОБЛ [61, 62]. Даже в отсутствие клинических исследований, оценивающих эффективность β2-агонистов длительного действия (ДДБА) или мускариновых антагонистов длительного действия (ДДАХ) при обострениях, рекомендуется продолжать прием этих препаратов базисной терапии во время обострения или начать их применение независимо от тяжести обострения [12]. Комбинация ДДБА и ДДАХ имеет преимущество перед монокомпонентной терапией, демонстрирует подтвержденное преимущество в уменьшении обострений при ее применении пациентами в стабильной фазе ХОБЛ [63]. Согласно современным представлениям, метилксантины не следует рассматривать в качестве первоочередной бронхолитической терапии обострений ХОБЛ. Имеющиеся данные не подтверждают существенного положительного влияния на функцию дыхания и клинические проявления при обострении, вместе с тем побочные эффекты могут иметь серьезные негативные последствия для пациента [12, 61, 64]. Внутривенное введение метилксантинов (теофиллин или аминофиллин) может рассматриваться как терапия второй линии, используемая при недостаточном ответе на ингаляционную бронхолитическую терапию. Использование теофиллина требует контроля уровня плазменной концентрации, побочных эффектов и потенциальных лекарственных взаимодействий [65].

Антибиотики. Антибактериальные препараты не обязательны при любом обострении ХОБЛ. Безусловно роль инфекции (бактериальной или вирусной) может быть значительной для части пациентов [66, 67]. В различных исследованиях подтверждалась относительная важность инфекций при обострениях ХОБЛ: вирусная и/или бактериальная инфекция была выявлена в 78% обострений ХОБЛ: у госпитализированных пациентов 29,7% таких инфекций были бактериальными, 23,3% – вирусными и 25% – вирусно-бактериальными [68]. В целом бактериальная инфекция может стать причиной обострения ХОБЛ примерно в половине случаев [69, 70].

Лечение антибиотиками при обострении ХОБЛ показано, если у пациентов имеются по крайней мере два из трех основных клинических признаков обострения, включая гнойную мокроту, или если пациенту требуется искусственная вентиляция легких [12]. Гнойная мокрота является важным симптомом, повышающим вероятность успеха при применении антибиотика. У пациентов с гнойной мокротой в период обострения более вероятно выявление положительных бактериальных культур [71], и это может быть использовано в качестве маркера для назначения антибиотиков [72]. Сочетание отдельных клинических и лабораторных маркеров может быть более полезным для предсказания успешности антибактериальной терапии. Так, в одном из исследований показано, что если у пациента с обострением ХОБЛ отсутствовала гнойная мокрота и уровень С-реактивного белка (СРБ) не превышал 40 мг/л, то вероятность неудачи лечения без применения антибиотиков составляла всего 2,7%. В то же время, если при наличии гнойной мокроты и значительном повышении уровня СРБ (более 40 мг/л) антибиотик не назначали, вероятность неуспеха терапии повышалась до 63,7% [73]. В целом, если у пациента с обострением ХОБЛ исключено инфицирование SARS-CoV-2, СРБ является хорошим маркером бактериальной инфекции, позволяющим сокращать необоснованное назначение антибиотиков без увеличения риска неблагоприятных исходов обострений [74, 75].

В современных условиях, когда повышение уровня СРБ ассоциируется с вирусной инфекцией, в частности с COVID-19, прокальцитонин может рассматриваться в качестве инструмента для определения показаний к антибактериальной терапии, однако требуются дополнительные исследования для уточнения места этого маркера в выборе лечения обострений ХОБЛ. В настоящее время имеются весьма противоречивые данные, в первую очередь у госпитализированных пациентов, в особенности пребывающих в отделениях интенсивной терапии. Так, использование прокальцитонина в алгоритмах назначения или отмены антибактериальной терапии ассоциировалось с более высоким уровнем смертности у пациентов с тяжелым обострением ХОБЛ [76].

Глюкокортикостероиды. Эндоброн-хиальное и системное воспаление усиливаются во время обострения ХОБЛ. Было показано, что системные глюкокортикостероиды (ГКС) повышают эффективность лечения в стационарных и амбулаторных условиях, сокращают продолжительность пребывания на больничной койке и приводят к более быстрому улучшению функции дыхания и симптомов во время обострения [77]. В целом продемонстрировано, что короткие курсы системных ГКС столь же эффективны, как и более длительные [78], а пероральный путь введения эквивалентен внутривенному [79]. Вместе с тем длительные курсы ГКС ассоциируются с повышением частоты побочных эффектов. Так, увеличивается частота инфекционных осложнений, в частности пневмоний, венозных тромбозов, переломов вследствие остеопороза, смертности от любых причин [80–82]. В различных исследованиях сообщается примерно об одном дополнительном побочном эффекте на каждые 6 пролеченных пациентов [83], причем особенно часто встречается гипергликемия. У пациентов, находящихся в отделении интенсивной терапии, более высокие дозы ГКС могут ассоциироваться с увеличением времени пребывания в стационаре и такими побочными эффектами, как гипергликемия и грибковая инфекция [84].

Муколитики. Муколитики применяются для улучшения мукоцилиарного клиренса при ХОБЛ, но также обладают антиоксидантными и противовоспалительными свойствами. Важным звеном патогенеза обострения ХОБЛ является оксидативный стресс, и антиоксидантная терапия может замедлять снижение функции дыхания у пациентов. N-ацетилцистеин (NAC) обладает способностью не только изменять реологические свойства мокроты, но и ингибировать выработку оксидов, повышать уровень антиоксидантов [85] (рис. 4). В последние годы благодаря широкому клиническому применению все больше результатов исследований показывают, что NAC может значительно снизжать частоту обострений ХОБЛ [86, 87]. NAC является муколитическим средством – предшественником L-цистеина и восстановленного глутатиона (GSH). Характеристика NAC как предшественника GSH является важным фармакологическим свойством этого препарата, поскольку позволяет восстанавливать пул внутриклеточного восстановленного GSH, который истощается в условиях оксидативного стресса и воспаления при ХОБЛ [88, 89]. Показано, что пероральный прием NAC в дозе 600 мг/сут. в течение 5 дней значительно увеличивает концентрацию GSH в бронхоальвеолярной жидкости по сравнению с контрольной группой (р<0,05 через 1–3 часа после последней дозы NAC) [90].

NAC также обладает прямым действием в отношении свободных радикалов, таких как гидроксил-радикал (OH), пероксид водорода (H2O2) и супероксид анион (O2-) [92]. В рандомизированном плацебо-контролируемом исследовании лечение NAC значительно снизило концентрацию H2O2 в выдыхаемом воздухе пациентов со стабильным течением ХОБЛ [93]. На фоне длительной терапии NAC в дозе 600 мг/сут. в течение 12 месяцев наблюдалось прогрессирующее снижение концентрации H2O2 по сравнению с исходным уровнем, которое достигло статистической значимости после 6 месяцев лечения (р<0,03). После 9 и 12 месяцев лечения концентрация H2O2 в выдыхаемом воздухе была соответственно в 2,3 и 2,6 раза ниже у пациентов, получавших NAC, по сравнению с пациентами, получавшими плацебо (р<0,04 и р<0,05 соответственно).

Благодаря своей свободной сульфгидрильной группе, которая придает NAC способность разрывать дисульфидные связи кислых мукополисахаридов мокроты, препарат широко используется для снижения вязкости и эластичности бронхиального секрета [94]. Многочисленные свойства NAC позволяют применять этот препарат в различных клинических ситуациях, включая обострение ХОБЛ. Так, в проспективном интервенционном исследовании пациентов, переносящих обострение ХОБЛ, добавление к терапии 600 мг NAC 2 раза в сутки (высокая доза) к протоколу лечения приводило к значительному улучшению клинических симптомов, включая свистящее дыхание и одышку, а также потребность в носовой кислородной поддержке (р≤0,05) [86].

Недавний мета-анализ исследований был проведен для того, чтобы оценить способность NAC улучшать клинические симптомы и функцию дыхания у пациентов с обострением ХОБЛ [95]. В анализ были включены 15 исследований с участием 1605 пациентов, переносивщих обострение, которым к терапии добавлялся NAC в дозе 600 мг/сут. перорально. На фоне лечения проводилась оценка динамики симптомов обострения, показателей спирометрии (ОФВ1, ОФВ1/форсированная жизненная емкость – ФЖЕЛ), активности глютатион-S-трансферразы (GSH-ST), способности ингибировать гидроксильные и супероксидно-анионные радикалы. GSH-ST – это изофермент, катализирующий конъюгацию GSH через сульфгидрильную группу с электрофильными центрами, что приводит к восстановлению повреждения фосфолипидных мембран, вызванного свободными радикалами, ингибированию микросомального перекисного окисления; активность GSH-ST отражает состояние оксидативного стресса. Мета-анализ подтвердил, что NAC может способствовать улучшению симптомов у пациентов с обострением ХОБЛ (уменьшение кашля, экспекторации мокроты и одышки было статистически значимо по сравнению с контрольной группой (ОР=1,09; р<0,0001, рис. 5). Было выявлено, что ОФВ1 достоверно повышался в лечебной группе по сравнению с контрольной: средняя разница составила 30,63 (95% ДИ: 25,48–35,78; p<0,0001). Улучшение функции дыхания и симптомов объяснялось исследователями уменьшением повреждения дыхательных путей, вызванного оксидативным стрессом, уменьшением ремоделирования дыхательных путей вследствие воспаления, а также улучшением реологических свойств мокроты, облегчением ее экспекторации и уменьшением на этом фоне бронхиальной обструкции. Активность GSH-ST в лечебной группе также была заметно выше, чем в контрольной: среднее различие составило 3,10 (95% ДИ: 1,38–4,82), и разница была статистически значимой (p=0,0004). Основными ограничениями описанного исследования, по мнению авторов, являются малый размер выборки и то, что на динамику симптомов и функциональных параметров могли оказывать влияние различные факторы, такие как исходное состояние пациента, антимикробная терапия и нутритивная поддержка. Вот почему требуются дальнейшие рандомизированные контролируемые исследования для оценки эффективности NAC при обострении ХОБЛ.

Заключение

Опыт, накопленный за годы пандемии, свидетельствует, что пациенты с ХОБЛ подвержены высокому риску, связанному с последствиями COVID-19. Описаны отдельные патофизиологические механизмы, которые делают пациентов с ХОБЛ более восприимчивыми к вирусным инфекциям и повышают вероятность микротромбозов, внутрилегочного шунтирования и вторичной бактериальной инфекции. Это приводит к росту госпитализаций и смертности больных ХОБЛ. Задача врачебного сообщества использовать все доступные и эффективные способы, чтобы защитить пациентов по возможности до встречи с вирусом SARS-CoV-2, вызывающим новую коронавирусную инфекцию. Необходимо своевременно диагностировать ХОБЛ и ее обострения, объяснять пациентам важность мер профилактики COVID-19, назначать полноценную (в первую очередь бронхолитическую) базисную терапию в период стабильного течения ХОБЛ, как можно быстрее и эффективнее устранять симптомы обострения заболевания. Муколитическая терапия не является первостепенной фармакологической опцией при ведении пациента с обострением ХОБЛ, однако добавление эффективного муколитика, такого как N-ацетилцистеин, может приводить не только к снижению вязкости бронхиального секрета и улучшению его экспекторации, но и (за счет многочисленных полезных свойств) к уменьшению клинических симптомов и увеличению функциональных показателей. Кроме того, терапия N-ацетилцистеином может снижать риск будущих обострений ХОБЛ.